Creating Magic in the Western Sahara: ARTiFairiti, 2018

Federico Guzmán (AKA Fiko) has become an iconic figure in Western Sahara, utilizing the platform art offers as a vehicle to promote peace and social change to the Saharawi people. Guzmán treads between a soldier of solidarity and curator of cultures emphasizing on gatherings, art, and experiences that will induce an exchange of ideas and collaborations between artists and wherever his projects realize, and the local community.

For twelve years Guzmán has co-organized ARTifariti The Arts and Human Rights Encounters of Western Sahara in the African desert “as a way to explain the circumstances of the Saharawi people ” creating a “weapon of visibility” to a story not globally known by many nor should be hidden from the public eye: and with projects such as ARTifariti one sees the opportunity to include foreign narratives and artists distanced by unfavorable political circumstances into the art world”.

The selected artists demonstrate couth in human rights and its relevance within the arts, but more importantly “are confronted a reality” that is life-changing from personal to professional, receiving a surreal cultural exchange with fresh perspectives and resilient power from the Sahawari people (especially from the matriarch figure whose role is to lead the community).

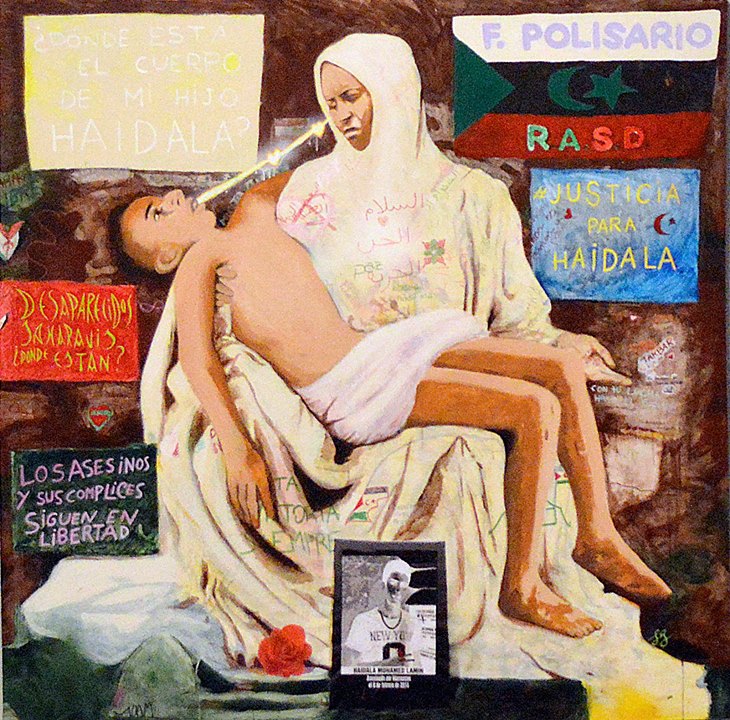

La Piedad Saharaui. Takbar Hadi y su hijo Haidala Mohamed Lamin (The Sahrawi Madonna. Takbar Hadi and her Son Haidala Mohamed Lamin). 2016. Mixed media / canvas. 200 x 200 cm. Fiko 2017.

During 2018’s visitation in the Sahara, the artists delve into intense creative processes of art-making, finally exhibiting and documenting the work(s). Collaborations are accessible on the list of actions to accomplish plus participating in workshops, lectures, talks, and classes that take place in the refugee camps and in the Liberated Zone.

This year Una Poesia Hecha por Todos (A Poem Made By All) marks a special edition of ARTifariti, making it the first for the artist to reside in the homes of nomadic families.

I asked Guzmán a few questions on his artistic endeavors, interest in the Western Sahara region and predictions on a change in the future.

Concert by Pililli Narbona and Ballena Gurumbé at Tuiza, The Cultures of the Bedouine Tent. Crystal Palace of the Retiro Park, Madrid. MNCARS. Fiko 2015.

BB: Hello Fiko, how’s it going?

F: Salam Aailekum Beláxis (may peace be with you). I am doing great, and specially excited with this year’s edition of the Arts and Human Rights Festival, because we are coming back to Tifariti, in the deep Saharan desert, where the Festival was born twelve years ago. Since then, ARTifariti has become a collective action against the Moroccan “Wall of Shame”, a 2,800 Km. armed berm that fractures Western Sahara in two, separating Saharawi families between occupation and exile. These encounters are a tool to reclaim the rights of individuals and peoples to their land, their culture, their roots and their freedom. ARTifariti is an international meeting of artists, activists and social scientists that opens up a space of struggle for the realization of human rights through artistic practices.

BB: What was the source of inspiration to this year’s edition Una Poesia Hecha por Todos? Were you reading any classic novels or another manuscript that may have influenced the direction or title?

F: First of all, poetry –together with music– is the main art form of this nomadic people. As an oral tradition that does not depend on artifacts to carry its message, poetry has had a strong stream of expression that is followed today by The Generation of Friendship: Saharawi poets in the diaspora, writing in Hasaniya and Spanish, who “intend to convey the suffering of their people, united by stories of shepherds who got lost chasing their dreams behind a cloud”. Some of them are Sukeina Aali-Taleb, Alí Salem Iselmu, Limam Boisha, Mohamed Alí Alí- Salem, Bahia Mahmud Awah and Zahara Hasnaui. “Some times desires / are as inmense / as the throbs / of this empty specter”, the poem “How to Atract the Rain” by Limam Boisha. On the other hand, A Poem Made By All refers to the innate collaborative nature of the Encounters. In the short days that international artists share their experience with the Saharawi people there is a strong commitment to solidaritiy and collective co-creation. This attitude is inspired by the traditional concept of the “Tuiza” in the bedouin society. In Hassaniya Tuiza means solidarity collective work: coming together, participating and building something jointly. Therefore, Tuiza is the essence of this project as a space for hospitality and conversation between cultures, workshops and other collective activities that take place during the Festival period.

We should be aware that since ancient times, Sahrawi women have enjoyed great recognition in the tribes. It was based on the social awareness that their work is very heavy and necessary for the life of the community. The education of girls meant a great emphasis on tasks that involve specialization: different types of fabric weaving, building long strips of camel wool for the manufacture of jaimas and food preparation. Women were also responsible for transporting water and gathering firewood; they also took care of the goats and milk the camels. Women get together in a Tuiza and it is a moment of celebration, of sharing the news around the camps, and also the space where important political decisions for the community are taken. That is why this “collective work” is one of the pilars of the life in the desert.

Finally, A Poem Made By All will be the resulting document that compiles all the works and interventions of the participating artists in ARTifariti 2018, that will be delivered in hand to the Special Rapporteur on the Field of Cultural Rights of the United Nations in Geneva, Ms. Karima Bennoune. So she can have a firsthand account of a people that is struggling with the peaceful weapons of art, culture and education to bring about their right for self determination for Western Sahara, the only colony in Africa that never got its independence.

La tierra nuestra casa (Earth Our Home). Painted steel, 200 x 600 x 600 cm. Wilaya of Smara. Saharawi refugee camps near Tindouf, Algeria. Fiko 2011.

BB: When were you first exposed to the Sahawaris? Did you meet someone during an exhibition, or perhaps when you were traveling that informed you on the problematics, or is this a familiar narrative because the Spanish have had strong ties with the Sahawari people?

F: I vaguely remember being twelve years old and hearing on TV about the “Green March”, the Moroccan military invasion that annexed the Spanish ex-province. They were explaining that Spanish troops were giving over the territory to Morocco with an honorable withdrawal of the Spanish army. Obviously, a lie and an absolute atrocity. But I didn’t understand then the dimensions of this calamity. Since then, I never studied this regretful part of our colonial history in my Spanish school nor in universitiy. There is a planified shroud of media silence over this tragic conflict that stands as the most shameful and catastrophic disaster in recent Spanish history.

Many years later, I met Fernando Peraita, the president of the Asociation of Friendship With the Sahrawi People of Seville. Fernando is an extraordinary person. Engineer as a profession, visionary activist as his passion in life. He was a conscript doing his military service in Laayoune in the moment of the Spanish withdrawal from the territory. He witnessed the carnage inflicted on what he considered friends and compatriots. Back in Spain, he became the mastermind behind the creation of an arts festival in the desert. No one in the art world would be crazy enough to undertake such an improbable commitment. He always tells me with a wide smile: “we did it, because we didn’t know it was impossible”.

When I first arrived in the Saharawi refugee camps I learned that Western Sahara is the last remaining colony in Africa. After the withdrawal of Spain in 1975, neighboring Morocco illegally invaded the country, forcing its indigenous population, to live under occupation or face exile. Since then, the Saharawi people have been divided between two lands. Those living in the area bordering the Atlantic Ocean, which Polisario—the internationally recognized political representative of the Saharawi people in their struggle for independence— labels the “Occupied Zone,” endure an occupation violently imposed on them by the Moroccan government. There, Sahrawis live under constant threat of imprisonment and torture, with no UN Human Rights mandate in place. Meanwhile Morocco and its international allies plunder the land’s abundant natural resources of fish, phosphates, and oil.

BB: I am aware that many Spanish families (as well as from other countries such as Cuba, France, Algeria & Libya) have provided housing and support to the Sahawari people for educational advancements. Tell me how these interactions/exchanges have enriched the communities in Spain.

F: Yes, the exchange program Vacaciones en Paz has brought to Spain for more than thirty years thousands of young Saharawis between the ages of 8 and 12. The children learn Spanish, receive education, medical revisions and treatments, enjoy a nice weather and the comfort of hospitable Spanish families, away from the unbearable burning temperatures of the desert summer. On the other hand, it is the Spanish families and children who receive a lesson on human values –that in our societies have almost forgotten– from the young Saharwis. We could comfidently affirm that Vacaciones en Paz, with all the direct relation and communication between Spanish and Saharawi families has done much more for the transformation of the conflict that all the diplomatic negotiations held in the political sphere.

BB: How has your relationship to the Sahawaris and their culture affected your work? In 2015 Bedouin Tent was exhibited at Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. The work was smaller- scale reflection of what takes place in the Sahara during ARTifariti, which is quite lovely. Do you think your love and support to the Sahwari’s evolved your work to a new height, like an epiphany? It’s apparent that your comprehension of space and dynamics is prevalent in your current manifestations. It’s smashing! Bedouin Tent traveled through time and space, granting the viewer to participate in a setting that otherwise would be lost in one’s mind because they don’t have the opportunity to visit the Sahrawi community and feel that place and time in the world.

F: Definetely it’s been much more than a personal, artistic and political transformation. I have had many conversations and learnt about what life is like. I have spoken with people who fought in the war, others who crossed the desert while napalm bombs dropped around them, and family members who had their loved ones disappeared by Moroccan security forces. The most disturbing stories, however, were told by the younger generation who know nothing other than a life lived as a refugee. While humbled by their fortitude, I am appalled that the international community allows children to be born into a life where, there is no sense of home or future, only a life spent in purgatory.

BB: The name ARTifariti birthed from Tifariti: the region that divides the Sahawari from the Moroccan wall, an area swarmed with land-mines. Just the thought of this stresses me out. I can’t fathom peace of mind knowing a person is a few kilometers away from an explosion. How safe are the Sahwari’s from this area? I am impressed by their resilience and bravery. Was the name ARTiFariti a way to commemorate the history of Tifariti?

F: Yes, you have to understand that, traditionally, Tifariti was a crossing point of the caravans that wandered the desert. On the day that the UN inforced a ceasefire between Morocco and the Polisario, Morocco intentionally and brutally bombed the area with napalm and white phosporous, destroying all infrastructure and leaving no stone standing in Tifariti. Since then, this place has become a sort of “Guernika” for the Saharawis: a memorial emblem of violence and also of the resistance and freedom of a people. It is considered as a sort of “capital” of the Free Territories. There were enough geopolitical and emotional reasons to choose this precise place to hold a festival for peace, and for global human rights.

BB: Now that it has been twelve years, what does it look like for the Sahawari people’s declaration of independence? Do you think ARTifariti is facilitating their quest and do you believe ARTifariti could exist as a traveling exhibition with the United Nations?

F: The message at the core of ARTifariti’s ethos is PEACE, HUMAN RIGHTS and SELF-DETERMINATION, believing that Art can be a tool in developing a people’s international presence and domestic well being just as much as those NGOs that provide material and infrastructural aid. As the 2012 open call for participants to the VI ARTifariti festival presented it: ARTifariti is a working context in which artistic practices play a provocative, reflective and transformative role. The focus is the Sahara conflict, but from here expands into other territories, questioning any situation where individual and collective human rights are violated. ARTifariti is an appointment with artistic practices as a tool to vindicate Human Rights; the right of the people to their land, their culture, their roots and their freedom. It is an annual encounter of public art to reflect on creation, politics and society, and a point of contact for artists interested in the capacity of art to question and transform reality. ARTifariti also aims to promote intercultural relations, fomenting the interchange of experiences and skills between local artists and artists from other parts of the world in order to contribute to the international widespread coverage of the Saharawi reality. It provides a reflection point from the world of Art and Culture through direct knowledge and promotes the development of the Saharawi people through their Cultural Heritage. The festival is also seen by Saharawis as an assertion of their sovereignty over their country: it is a means of re-appropriation, even if it is undertaken mainly by foreign artists, as a kind or re-appropriation by proxy. ARTifariti is also seen as reinforcing a Hispanic-Arab culture that undoubtedly makes Saharawis unique, and feel unique, within the Arab world. As the Commander of the SPLA in the Tifariti region put it: ARTifariti is a means of exercising sovereignty over our territory [and] the liberated territory, besides contributing to the preservation of our national identity and our Spanish-Arabic culture. It is the foundation stone of a road that can only lead to freedom.

BB: What’s next for us globally Fiko? How can we trickle the right social change in society? The one where people will take responsibility to have the discipline and commitment to change themselves, not the other. We have a significant burden on our shoulders, but it’s an excellent one.

F: You are right. We are in the Century of the Big Transformation. We have in our hands the enormous challenge and historic opportunity to change the dream of the planet. I have the hypothesis that our human species is unconsciously willing its own collapse to force a jump into a higher level of planetary consciousness. The Saharawi conflict is not a problem of “a few poor victims far away in a corner of Africa”. It is the extreme expression of the dysfunctional way in which the patriarchal colonial matrix forces life in our societies. I don’t think we will transform conflict from the same level of consciousness in which it was created. We have to transcend as a human family that is intrinsically part of the body of the loving super organism that is Mother Earth. A new world will have to be degrowing, self-managed, anti-patriarchal and internationalist. Or it won’t be.

Written by Beláxis Buil

Edited by Abel Folgar