- 10 years ago

-

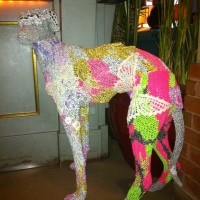

The Soho Grand Hotel was the place to be for art enthusiasts on Wednesday September 10th as New York’s fashion week kicked off. Known as a feminist artist and yarn bomber, Olek’s latest show, “Reality What a Concept” opened to rave reviews. The show, curated by the uncompromising Natalie Kates, included performance pieces in addition to the crocheted playground created by Olek.

Olek’s work will be featured at the hotel through the end of the year. The show is part of a year long curatorial series by Natalie Kates which includes an upcoming exhibition by artist Ron English.

– Frank Jackson

- Artist, Olek

- Artist, Olek

- Artist, Olek

Latest News

- 10 years ago

-

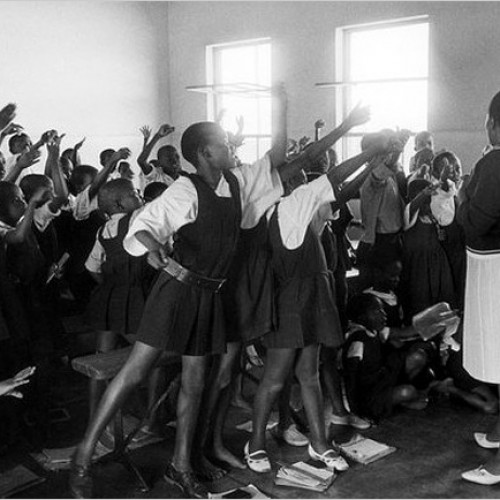

I recently saw “Ernest Cole Photographer” which is on display through December 6 at the Gray Art Gallery at New York University. This is the first solo exhibition of Cole’s work in the US which was organized by the Gothenburg’s Hasselblad Foundation. The exhibition features 120 photograph which stem from his time working as a photojournalist in South Africa in the late 1950 and 60s.

Cole was born in 1940 in the township of Eersterust, Pretoria. Several years later his family was forced to relocate to Mamelodi as a result of the Group Areas Act of 1950. Growing up in a very politically charged time in South Africa greatly affected how Cole would come to view the world. Cole began taking photographs at a young age which would turn into a life long passion for him.

In 1958, Cole began working as a dark room assistant at DRUM Magazine, a publication geared towards black lifestyle located in Johannesburg. Working under the supervision of fellow photographer and artist Jürgen Schadeberg, Cole started to become politically active. During this time he met various artists, musicians and political leaders who were also fighting in the anti-apartheid movement. With Schandeberg’s help, Cole enrolled in a correspondence course with the New York Institute of Photography. Cole would go onto to document the political situation in South Africa while working as a photojournalist for various newspapers. These photographs would become the basis of his 1967 book House of Bondage which was banned in South Africa.

In 1966, Cole was arrested by the police and was given to options–to either join their ranks as an informant or be sent to prison. Given the options the police gave him, Cole left for Europe taking only necessities and the layouts for his book. He spent the next 23 years of his life in exile shuttling between Europe and the U.S. He died in New York City in 1990.

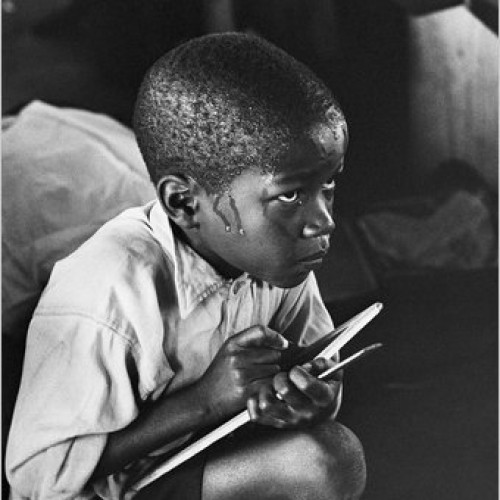

The 120 photographs on display take up two floors of the gallery’s space. The sheer volume of them and many of the scenes they depict are overwhelming. They are moving, hard to sometimes confront and expose a very different side to South Africa and the way it has come to be known in a modern context. Cole’s beautiful compositions showcase many day to day events that were common to South Africa at that time such as lines of male workers waiting to get paid to children in classroom settings with no desks and chairs struggling to get through the lessons at hand. Within the image “Boy in School” for example, a young South African squats with a notebook in his lap, sweating, straining to pay attention. Images such as these offer a complex and difficult illustration of a time period that still haunts South Africa today.

“Boy in School” Image courtesy of the Gothenburg’s Hasselblad Foundation

“Boy in School” Image courtesy of the Gothenburg’s Hasselblad FoundationCompositionally, Cole’s photographs are stunning. They capture very intimate moments among various walks of life within South Africa while depicting a very specific sociocultural time. It is both their specificity and the historical importance that this images carry which only add to the importance of Cole’s work. Cole’s ability to capture intimate moments between mother and child as well groups of prisoners and workers not only underscore his talent as a photographer but also his regard for the human condition. Cole’s compulsion to document the world around him and those most affected by the oppressive regime of apartheid is one of the most powerful elements of the show. Because the pictures are in black in white also reinforces the racial issues that were occurring at this time.

Image courtesy of the Gothenburg’s Hasselblad Foundation

Image courtesy of the Gothenburg’s Hasselblad FoundationGiven the recent events that occurred within Ferguson, Missouri last month with the death of 18 year old Michael Brown, the timing of the Cole show at Gray Gallery seems even more poignant. While these images and Cole’s background are tied to South Africa they also call into question the current racial landscape in the U.S and it’s history. This show harbored echoes of many iconic images of Civil Rights era photographer which originated during the same time period. Cole has left behind a visual record of what it was like to be black during apartheid in South Africa that will live on for generations. However it will take generations to come to terms with this harrowing time in South Africa’s history.

–Anni Irish

- 10 years ago

-

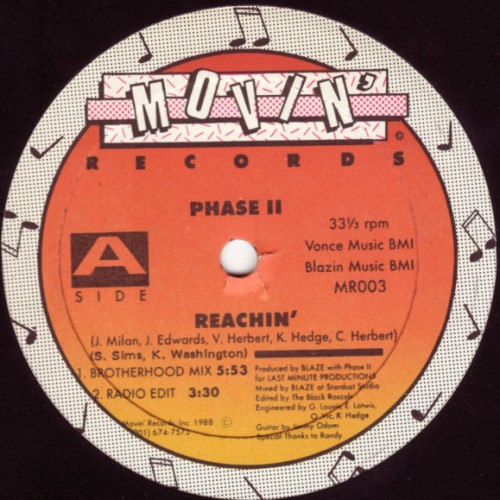

Strictly Rhythm. Nervous. Emotive. These seminal New York labels, along with a handful of others, evoke a time in the late ’80s and early ’90s when the local variant of house music, one that combined depth, emotion and soul with the raw rhythms that had been coming out of Chicago, took form. But there was one other local label that was equally influential—and it wasn’t even based within the five boroughs. Its name was Movin’ Records, a label (and record shop) led by Abigail Adams and based in East Orange, New Jersey.

Between 1987 and 1995, Movin’ released some of the most beloved songs of the era—Phase II’s stone-cold classic “Reachin’” among them—and its lineup of vocalists and producers and included such notables as Kerri Chandler, Kenny Bobien, DJ Pierre, Ce Ce Rogers, Blaze’s Kevin Hedge and Josh Milan, Ace Mungin and Tony Humphries. That last name is key: A symbiotic relationship formed between the club that Humphries deejayed at, Club Zanzibar in nearby Newark, and Movin.’ Though they were both just a few miles west of Manhattan, the Movin’-Zanzibar affiliation resulted in a sound with a different feel than what was going down in Gotham, a feel that amped up the gospel- and R&B–tinged passion beyond what the big city had to offer. It’s a style of house generally referred to as the Jersey Sound—and its effects can still be felt on the club music of today. I recently had the pleasure of speaking with the gracious and friendly Adams, her love of the music still shining brightly.—Bruce Tantum

How did Movin’ Records get started?

Abigail Adams: Movin’ was an interesting journey. I never had the intention of doing a record shop or a record label. It actually started as a roller-skating store. I used to go to the Roxy in Manhattan and roller skate. I loved it, but I couldn’t find a place in New Jersey to buy skates, so I opened Movin’ Skates in the early ’80s. We built custom skates and did skate rentals. My partner and boyfriend at the time was a DJ, and he had some 1200s in the back of the shop. We were also going to the Paradise Garage, so we were pretty up on the sound, and we used to go into the city—to places like Downstairs, Downtown, Vinylmania, Rock & Soul—to buy records and play at the shop. People would ask, “Oh wow, what’s that cut?” I’d say, “Oh, I can get it for you!” So I would literally just buy it from Charlie Grappone at Vinylmania or whoever, bring it back to Jersey and sell it for a quarter or fifty cents more.And it just progressed from there?

Abigail Adams: Yeah. More and more people started asking for records, so I started buying direct. My network started opening up. I knew people like Judy Weinstein and David Morales and all the people at [record pool] For the Record, Larry Levan and I became friends, and so on. But the main people were Danny [Krivit] and Julio at the Roxy. Those were the two who really schooled me about music. And they got me, hook, line and sinker. So basically, the record store just kind of developed organically.Abigail Adams: Who was coming to the shop in those early days?

Well, there were a lot of very cool people in that neighborhood back then, people like Queen Latifah, Naughty by Nature, Redman, Lauren Hill…they were all teenagers then, and they all kind of grew up in my store. I was listening a lot to Timmy [Regisford] on WBLS and Tony Humphries at Kiss FM, which had so much impact at the time. There was so much freedom on the radio back then; those guys could play whatever they wanted. This was about the time I started going to Zanzibar. The record store had really taken off by that time; we were really on the map. Knowing the DJs was really important, so I would know what was up and coming. Tony would play something that wasn’t out yet, I’d know about it and know when it was coming, and then the DJs and record buyers would know about it—and then we would finally get it. That whole waiting experience was just so magical, and you don’t really have that feeling anymore. Songs come out instantaneously, and then it’s on to the next one. Sometimes we’d have to wait three or four months for a record—which would make it so much more wonderful when you finally got it.How did the store morph into a label?

Abigail Adams: A lot of people would come into the store with stuff they had made. Boyd Jarvis, in particular, just had so much stuff. So we put out that first record [1987’s “I’ve Got the Music,” attributed to Before the Storm Featuring Boyd Jarvis]. That was basically how that all began.Tell me a little more the relationship between Tony Humphries and Movin’.

Abigail Adams: Tony, Zanzibar and Movin’ had a similar relationship as the one between Larry Levan , the Paradise Garage and Vinylmania. I’d know what Tony was playing, we’d know when it was coming, then we would have it in the store, and people would come in to buy it after hearing it at Zanzibar. It was a great relationship for all of us, really. It really helped to solidify things. Finally, in ’89, Tony, [Zanzibar manager] Shelton Hayes and I decided bring some more focus to this great music that was coming out, this music that we had been calling the Jersey Sound. We did these parties at the New Music Seminar, and we were flabbergasted by the amount of people who came out—people from all over the world! I actually felt that the music was accepted much more overseas, places like England and Germany. They really liked the soulful, lyrical, spiritual-based sound—something that was different than what Chicago or Detroit that were doing, and it really connected with them, particularly in the U.K.Who were some of the artists associated with the Jersey Sound?

Abigail Adams: There’s a lot! There was Smack Music, who worked with Kyze and Adeva; Backroom Productions with Jomanda; Boyd Jarvis, even though he’s from New York City; Ace Mungin, who put out “Let the Rain Come Down” as Intense; Paul Scott and Shank; Kerri Chandler and, of course, Kevin Hedge and Josh Milan from Blaze. Kevin actually worked at the store in the early days. I can remember talking to Josh when he was struggling as to whether he should do secular music or not, and what it would like for someone who had come up through the church to be doing club music. I could keep going; there was so much talent and great music that was coming out of New Jersey, and more often than not, when the story about the music of that period is told, does not get the props that it should.Why did you end up shutting down Movin’ Records?

Abigail Adams: There was a shift in the scene. The neighborhood that my store was in was really going downhill; there was a shooting in the gold store that was right next to my record store. But the main reason was that my daughter was born in ’92. But I was always very present at the record store, and to spend time with the baby and be at the store just wasn’t working. Finally, I got the opportunity to work with Queen Latifah. Vinyl sales were going down at that point, anyway. Charlie from Vinylmania always told me that I got out at the right time; he was actually very envious! A few years ago, I actually got back in on the management side, working with Mikki Afflick, Jihad Muhammed, Duce Martinez, Kenny Bobien and Francesca Magliano, and that was awesome. We had a few great parties, and it was so much fun. But house music, as much as I love it, is not a big money maker anymore, which is sad. But it was a great time.Abigail Adams: What are you up to nowadays?

I work at CustomInk, an amazing online custom-apparel company for groups and occasions. We are one the top ten best place to work companies in Fortune Magazine. My job is to run fun events at work and make sure all employees are happy, safe and well taken care of. It’s a great job. I truly miss my music, family, and the scene—but it will always be close to my heart.

- 10 years ago

-

Beth Fiedorek has been creating psychological narrative paintings and performance based work since 2007. Fiedorek who is a graduate of Yale, tackles issues surrounding everyday experiences while also commenting on “the improvement oriented culture” we live in within her art. Beth’s introspective and insightful approach to the art making process adds a level of complexity to the work she is generating. Fiedorek who has lived in Brooklyn since 2012, has taken part in the Gowanus Open Studios as well as performing in festivals such as FIGMENT, which occurred this past June.

I recently spoke with Fiedorek about her art making process, what some of the challenges she has faced as a working artist have been and her take on the Brooklyn arts scene.

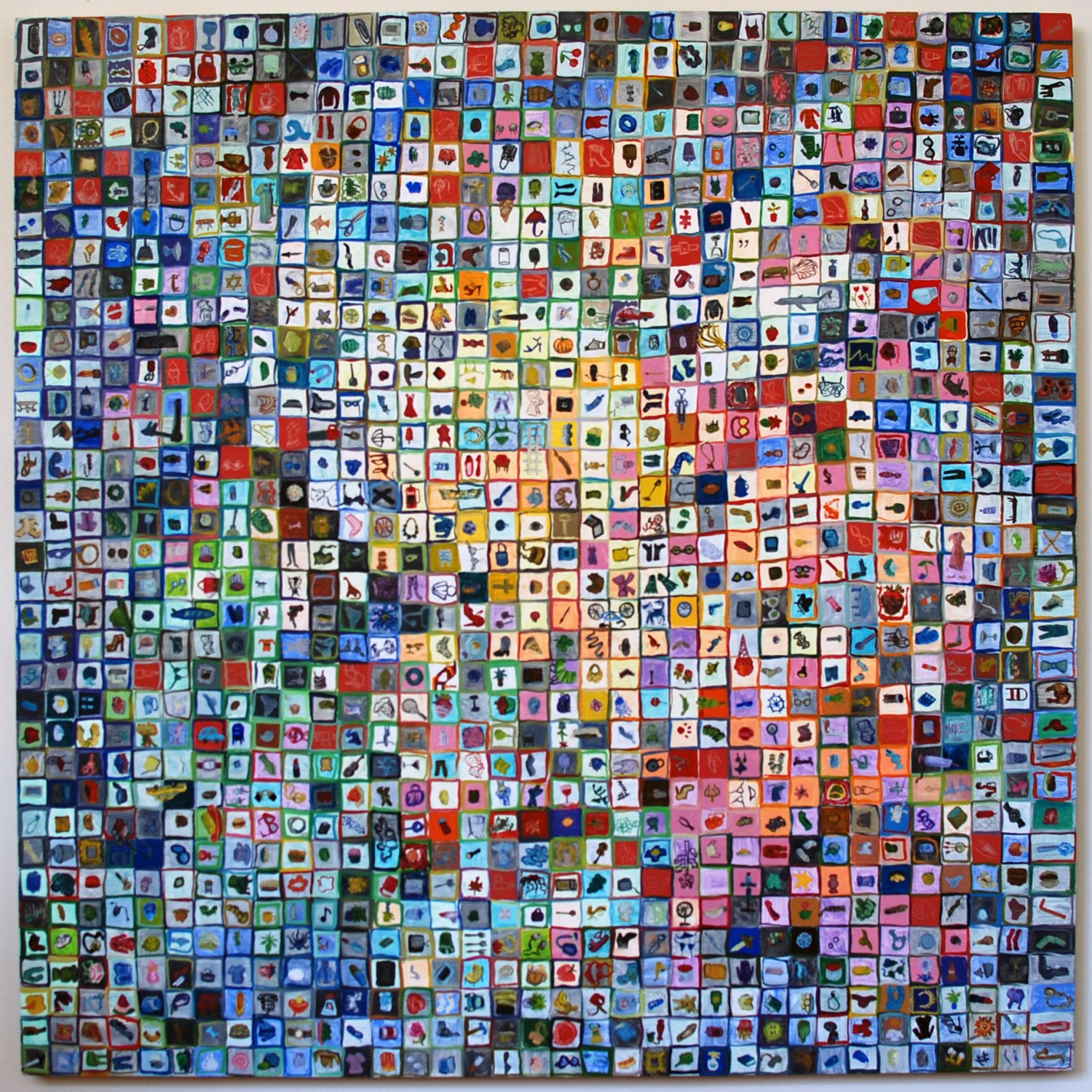

Something Invisible to Others, Oil on MDO board, 48″ x 48″. Image courtesy of Beth Fiedorek.

Something Invisible to Others, Oil on MDO board, 48″ x 48″. Image courtesy of Beth Fiedorek.Anni Irish: How did you get interested in art?

Beth Fiedorek: I always liked making things, ever since I was really young. I have found that materials tend to speak to me, sometimes more so than people which can prove to be awkward.

As I’ve gotten older, making art has become more about communicating and processing experiences. Figuration and materials carry symbolic energy that I try to use thoughtfully, highlighting strange moments I find intriguing. In painting, there are psychological narratives that emerge over time and it is not always something you can control. For me, the process and re-evaluation of materials are deeply important for civilization precisely because of this impulse to publicly yet introspectively reflect on what you feel using the physical matter at hand . But I also find the seriousness of this purpose is not something a painter can think about all the time while making the work.

A.I.: While doing your undergrad at Yale, how did you decide on painting as your concentration?

B.F.: The painters were the most fun and their critiques were always unpredictable and weird. Painting is intimate because of the combination of physicality and isolation. You are experiencing the process alone, but you also can’t hide, and I have always liked that.

A.I.: Because the art scene has evolved so much in even the last fifteen years and with this push to now have an interdisciplinary/mixed media approach to work, what do you think that has done in terms of labeling yourself as a particular kind of artist? Do you think that is limiting on some level?

B.F.: The interdisciplinary element of much contemporary practice is very different from how I was trained, but I think it is important. I am not sure if it is beneficial and I am still deciding how I feel about it because I am not sure where this will end up. If all artists ended up making work like Chris Burden in say his now infamous 1971 piece Shoot, the interdisciplinary push might not be as beneficial.

However, I am grateful that I am able to pursue transmedia projects, both for the projects themselves and because these can inform the way I approach traditional media. I do not think it is limiting, but the disparity between the vagueness of being an “artist” versus the specificity of making a successful artwork can be challenging. Anything is possible, which means that individual’s focus is very important. I think this echoes the ambivalence of modern living in general–you could conceive it as a rubber band mentality.

A.I.: How would you describe your studio practice?

B.F.: Painting as performance, with psychology.

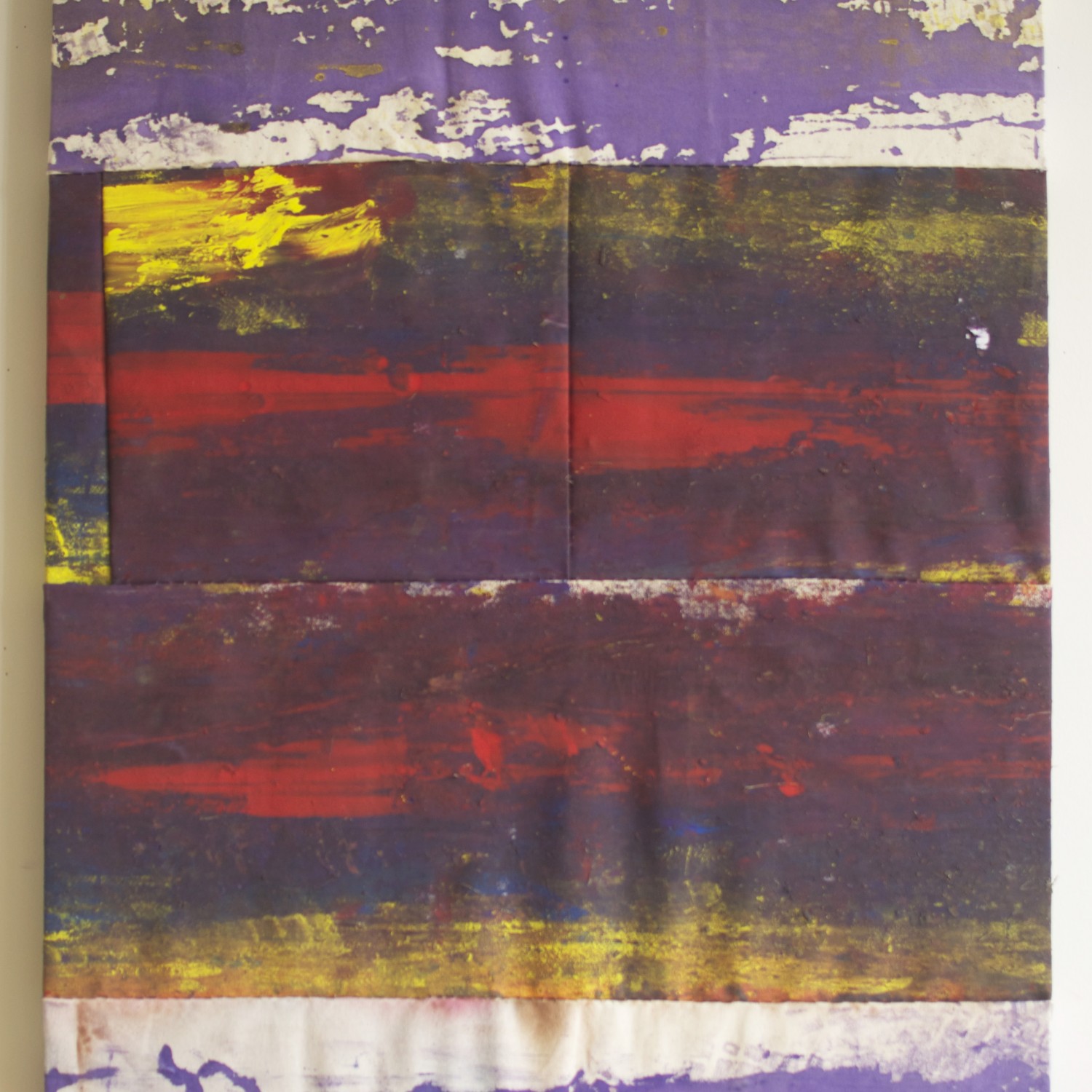

Girls by Pool: Framing Interrogation Situation, Mixed media on linen, 31″ x 24″. Image courtesy of Beth Fiedorek.

Girls by Pool: Framing Interrogation Situation, Mixed media on linen, 31″ x 24″. Image courtesy of Beth Fiedorek.A.I.: That’s interesting, where does the performative element come in for you? In the physical painting process or somewhere else, like in your performance piece Paintmatic?

B.F.: Definitely both. There’s a rhythmic energy to making paintings that is very performative, though not in the same way as traditional forms of performance like dance or theater. I also pay a lot of attention to how bodies — my own and those of other peoples — react to my paintings. To me this is a kind of bodily communication which is linked to performance.

Paintmatic,Performance documentation from June 7, 2014. Image courtesy of Beth Fiedorek.A.I.: As an emerging artist in the Brooklyn area, what do you think some of the greatest challenges are that you have faced but also for other artists in similar situations?

B.F.: Time and money. Most often, time is a function of money as artists are so busy working to pay their bills and pay for their supplies that there’s very little time left for making the work. Affordable studio spaces are increasingly rare. I get angry about this because one of the reasons that New York is a desirable place to live is the vibrancy of the culture, the striving, visionary living, and the art scene.

I would encourage the people who make a little extra money to carve out some to support the lovable weirdos chasing the collective subconscious. There are lot of really good artists who are leaving New York, and there will be more. It is really a shame.

A.I.: Do you think there are any artist based models that are in play or cold be enacted, that could possibly remedy this?

B.F.: That’s tough. It used to be that commissions for the Works Progress Administration could carry an artist through the early stages of a career, but today’s public arts funding is at historically low levels. This probably has mixed outcomes, and ultimately artists need to self-advocate. A good example is Maya Hayuk pursuing legal action against the megabrands who have used her work for profit without remuneration. W.A.G.E. (Working Artists for the Greater Economy) is a group doing very interesting research surrounding this topic that could help to change the way people thing about these very issues.

A.I.: What are some books, artists or critics you are currently reading?

B.F.: I’ve been reading about Yvonne Rainer. Because I started making figurative paintings, and because I had this treadmill which was kind of a performance, I thought “I should really get into dance.” I took a series at the Mark Morris Dance School in Fort Greene. It was great! I’ve been reading Carrie Lambert-Beatty’s book, Being Watched, which I really love for the title and for the way dance is related to other post-1950s art such as Fluxus. Through Lambert-Beatty, the dances might in some ways start with the politics of spectactorship but are ultimately about banality, documentation and the shared structure of daily life. A combination such as that sticks with you.

Sharon Butler’s blog on painting, Two Coats of Paint is great. She is a painter and her perspective is broad, but also intelligent, with a sense of humor. I’ve also become interested in the artist Lucio Fontana, recently but that might be a religious thing, so let’s not get into it.

A.I.: Given the way the arts have exploded in Brooklyn in recent years, how would you characterize the fine arts within this larger movement?

B.F.: Interesting question! I think the fine arts field is really hard to categorize because individual practices can be so different. Also, especially given the interdisciplinary element, there can be a lot of overlap between the fine arts and other fields. There are a lot of people who make music and also make drawings or paintings; there are a lot of fine artists who also are in bands or performance groups.

That said, to me fine art seems to have always been a relatively small, tight-knit and welcoming, vaguely grumpy place. This is compared to something like experimental music or dance, which aren’t focused on inert materials, and require an audience and a performance and the whole formal setup along with a degree of explicit positivity. It’s possible that fine artists band together readily because we work alone. There are numerous interesting studio collectives and new spaces in Brooklyn run by fine artists — DEAD SPACE and Tiger Strikes Asteroid, a Philadelphia transplant, comes to mind. Maybe fine artists need this receptiveness to each other as a balance to our usual fragmentation.

Paintmatic Painting, 2014, Mixed media/Performance Documentation, 36″ x 30″. Image courtesy of Beth Fiedorek.

Paintmatic Painting, 2014, Mixed media/Performance Documentation, 36″ x 30″. Image courtesy of Beth Fiedorek.A.I.: What are some current projects you are working on?

B.F.: I’m gearing up to start a few large figurative paintings that move beyond the technology-focused imagery I’ve been using for the last couple years. There will also need to be some postcursor to Paintmatic, my treadmill that makes paintings. I’m excited!

To Learn more about Beth’s work check out her website and be sure to follow her on twitter.

—Anni Irish

- 10 years ago

-

AFP Arts Education Program had a great summer this year and we look forward to the start of the new school year! The summer music program wrapped up with a great session that included recording a new song, learning more about the recording and mixing process, and vocal instruction. As I mentioned in my last post, each participant was asked to choose a song to work on learning to sing. The selections were very interesting and varied, and we had a lot of fun working them out. AFP is also excited to explore the possibility of partnering with City Kids on some future projects and programs, which could open up some new possibilities.

In this summer’s last session of the AFP music program, we recorded “The Cut”, a new song by the band newly formed by the kids, called Static Vision. We set up all of the instruments in the music classroom at Humanities Prep, using tables as gobos to separate the sound sources a little bit. We mic’ed all of the drums and amplifiers, and recorded live together, a technique that is employed less and less these days in the age of overdubbing and “in the box” production. It was a great opportunity for the band to seek to achieve excellence as a group, and to focus on listening to each other, while performing with energy and accuracy. It’s a tall order, but it brought out the best in everyone, and we got a few near perfect takes, which we will be editing and mixing in sessions that will be held during the coming school year. As intense as the recording process was, everyone was eager to call an end to the recording part of the session in time to continue our vocal work. Each person came prepared to sing part of a song in front of the group, and to hear some criticism and suggestions. Ray Moreta chose “Jumper”, by Third Eye Blind, Alex Gonzales, “Blue Sunday” by The Doors, Jason McFarlane picked the Killers’ “Mr. Brightside”, and Gabriel Ogbennaya selected MC6’s version of the 50’s doo-wop classic “Runaround Sue”. Everyone was supportive of one another, and received the criticism eagerly and with maturity, which really impressed me. I gave everyone suggestions on how to breathe, on tone production, and on how to pick out the notes of a melody on the piano in order to cement the pitches in ones mind’s ear.

I’m looking forward to meeting up with Frank Jackson to make another visit City Kids at their new facility in downtown Manhattan. I met with acting ED Fred Begley last week, and it looks like there may be some great opportunities for City Kids and AFP to partner on some events and programs there, and throughout the city. We’re looking forward to designing some new offerings for the coming year, so please contact me if you have any suggestions or have a curriculum in mind to teach. Thanks, and enjoy the last few days of summer!