- 7 years ago

-

The title of Barnaby (aka Barney) Clay’s new documentary, SHOT! The Psycho-spiritual Mantra of Rock, says it all, really. This rambling, entertaining portrait of legendary music photographer Mick Rock is full of its genial subject’s own musings on his life and art. It also encapsulates the excitement and excesses of the heady musical era that Rock (barely) lived through and documented. For anyone with a passing interest in the rock scenes of the late 1960s through ’70s, this will be pretty fascinating stuff. For those, like myself, who remember wondering about the photographer whose impossibly appropriate name appeared on pictures of many groundbreaking artists, this will provide context, and then some. (For the record, the man’s given name is actually Michael David Rock.)

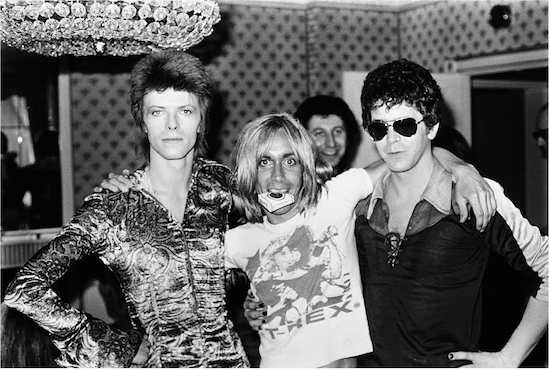

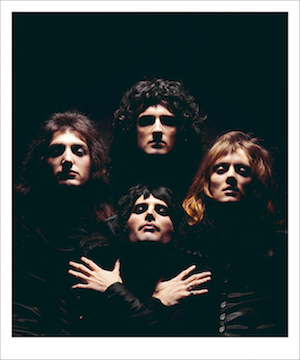

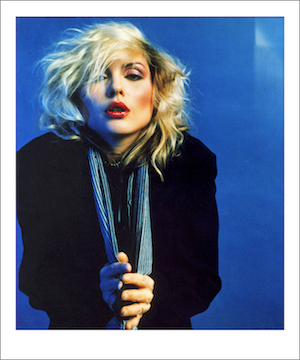

The film opens with present-day Rock (now in his late 60s) loading his camera at a live TV on the Radio show. He talks about his process, which—at its best—makes him feel like an assassin, “I’ve got my sights on you, gonna take you out.” Later he clarifies, “I’m not after your soul, I’m after your f-ing aura,” which might prompt an eye-roll, except that he really did capture the essence of performers (and friends) such as David Bowie, Lou Reed, Iggy Pop, Freddie Mercury and Debbie Harry, among others. For many awestruck kids, Rock’s images were their introduction to these genre-defying musicians.

The film takes us through a more or less chronological account of Rock’s career, interspersed with dramatic reenacted clips of the aftermath of his near-fatal 1996 heart attack. In addition to myriad iconic photos, many of them album covers, there are snippets of taped conversations with Reed and Bowie at the beginning of their careers, when they were still figuring themselves out.

Rock revisits Cambridge University, where as a student in the late 1960s, he was introduced to poetry and LSD, virtually the foundations of the era’s music. His first famous subject was local Pink Floyd founder/mad genius Syd Barrett. “I never felt like a voyeur,” Rock says, but was accepted as part of the burgeoning Cambridge youth scene—a dynamic that would mark his career and friendships.

Enter the early ’70s and David Bowie. Rock, whose fascination with the (then) startlingly androgynous singer resulted in some gorgeous early shots, becomes Bowie’s personal photographer, a distinction that would raise the profiles of both artist and photographer. He would develop self-professed fixations on several artists of that era, later shooting the emblematic live image that became the cover of Lee Reed’s Transformer LP; similarly, a photo of Iggy Pop in concert would come to represent Raw Power. Rock describes the sessions and resulting images with reverence and a little awe, as if he still can’t believe he was responsible.

He takes us through the advent of Glam, which celebrated bisexuality before any kind of mainstream acceptance, and describes how established artists such as Rod Stewart and Mick Jagger adapted the look, and did he himself. Not every shoot was a success, as is shown by some noble attempts that Rock unearths in his extensive archives.

It was when he chose to shoot Reed in New York over Bowie in Berlin in the late ’70s that Rock’s wild lifestyle grew wilder. He walks around present-day NYC and recalls many parties and little sleep. He was here for punk rock’s birth, shooting Talking Heads and Blondie, among others. (Reed’s early opinions of the Ramones and punk in general are quite amusing.) Finally the film catches up with the hospital gurney flashbacks and we get the details of his heart attack, which Rock believes was fitting punctuation to that part of his life.

Throughout SHOT!, Clay lets Rock muse, ponder, and generally try to make sense of his life, resulting in an indulgent film that sometimes seems excessive, which is sort of fitting, considering the subject matter. For such an introspective portrait, though, there is nary a mention of Rock’s private life, apart from a glimpse of him posing with wife Pati and daughter Nathalie. It would have been nice to meet the people who really know and love him.

The film closes with a 2015 photo shoot of Father John Misty and it’s clear that Rock still has the touch and still gets off on it. A whirlwind montage shows other current artists he’s shot, in addition to celebratory and poignant footage of recent sessions with Debbie Harry, Pop, Bowie and Reed. (The film is dedicated to the latter two.)

By the end of SHOT!, one feels almost as appreciative as Rock himself that he is still alive and shooting, given the very good odds that he wouldn’t survive his chosen profession.

SHOT! The Psycho-spiritual Mantra of Rock opens on Friday, April 7, at The Metrograph (7 Ludlow Street).

—Marina Zogbi

Latest News

- 7 years ago

-

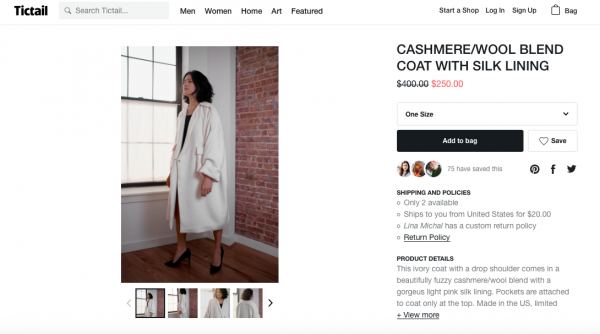

Here’s a kind-of-a-shocker: Ultra-hip social marketplace Tictail‘s brick-and-mortar flagship is that it’s not profitable.

Tictail Market is the brand’s one and only storefront, located in Manhattan’s Lower East Side — and surprisingly, the IRL store makes less in revenue than even many of the e-commerce site’s online independent sellers.

“The [brick-and-mortar] store makes about $50K a month; rent is $17K. Salaries and expenses bring us close to $8K, and that about covers it,” co-founder Carl Walderkrantz admits to Forbes readers.

So why is it important for an e-commerce site that pulls in millions of shoppers a week to offer an in-person experience that doesn’t generate significant profits?

Is it just to be able to flaunt kickass storefront gifs? (Courtesy of Tictail NYC)

Walderkrantz says that while the “future is moving toward online, the joy of shopping is still synonymous with an in-person experience” for many customers.

And in the tradition of other successful sites like Warby Parker, Bonobos and Away and less-that-lucative storefront was the best way to guarantee local awareness.

Photo courtesy TicTail

“Tictail Market literally put us on the map in this city,” says Walderkrantz, adding that it gives the brand “street cred.”

Originally, the DIY e-commerce site was developed as a means of giving entrepreneurs the ability to build online shops.

Photo courtesy of Tictail

It is now touted as the ‘easiest platform for discovering emerging brands around the globe’ — a gateway to thousands of under the radar brands from over 140 countries via an easy-to-navigate social marketplace. Brands include By Far (Bulgaria), Orphée (France), Humanscales (Sweden), and Lina Michael (Sweden)

Photo courtesy of Lina Michael/Tictail

And while mobile tools like Pinterest Visual Discovery continue to accelerate the switch from in-store browsing to online purchasing as we know it, Walderkrantz still believes that an IRL store is the best way to engage with a community of potential brand ambassadors.

“It’s a way to connect the brands and shoppers, and make the shopping experience feel a lot more personal” he says.

And the merits of a brick-and-mortal extend to larger brand partnerships, added social media activity through in-person events and flashy storefront art. “For each individual who visits your store, you should aim to reach another 50 through their extended network.”

Sounds worth it, eh?

- 7 years ago

-

The second film from Swedish director Kasper Collin, I Called Him Morgan is an evocative, beautifully filmed documentary of a remarkable life cut short and a remarkably fertile period in New York City’s jazz scene. In February 1972, acclaimed 33-year-old trumpeter Lee Morgan was shot to death by his common-law wife Helen in an East Village club. The murder shocked all who knew the couple, including Morgan’s fans and fellow musicians, many of whom tried to make sense of the tragedy afterwards.

Using interviews; gorgeous, iconic, black and white still photos; archival film clips, and moody reenactments—all underscored by a fabulous soundtrack—Collin constructs compelling portraits of both Lee Morgan and his common-law wife Helen, making their way in New York City’s hopping jazz scene from the late 1950s through the early ’70s. The story slowly builds up to that fateful night, providing details that many have apparently pondered for years. In doing so, Collin gives us a glimpse of the great talent possessed by Morgan, along with poignant memories of the people who nurtured and appreciated it. With its potent music, atmospheric footage of vintage NYC and artfully abstract recreations, the film also gives us a palpable sense of time and place.

Collin’s main resource is an interview that Helen gave to radio host and jazz scholar Larry Reni Thomas in 1996, a month before she passed away. This fortuitous conversation came about when Thomas was teaching adult education at a Wilmington, N.C., high school and she happened to be one of his students. The tape, shown being played on an old cassette player, has a scratchy, otherworldly sound, rendering Helen’s raw testimony all the more haunting.

We hear her story alternated with Lee’s, the latter mainly provided by musicians like one-time bandmate (Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers) and friend Wayne Shorter, who remembers first seeing teenage Lee playing with Dizzy Gillespie in the late 1950s. Very young and very talented, the Philadelphia-born Morgan is recalled as dapper and confident. We also hear excerpts from an interview that Lee himself gave in the early 1970s, in which he sounds as sharp and cool as his music.

Insightful interviews are provided by various bandmates and other luminaries in the scene, including Jymie Merritt, Bennie Maupin, Albert “Tootie” Heath, and Billy Harper, who chart the rise of Morgan’s career in New York, followed by his descent into heroin abuse and subsequent career collapse. Helen is recalled as a fixture in their circle, a strong presence (and great cook) who would provide meals to musicians in her 53rd Street apartment. Originally from rural North Carolina, she had escaped the privations of the farm, first moving to Wilmington where she had children while still in her teens, then to New York City when her first husband died. Her son, Al Harrison—only 13 years her junior—tells of first meeting his mother when he was 21, among other recollections.

It was Helen who took the fallen Morgan under her maternal wing, sending him to rehab, acting as manager and getting him club dates, and generally taking care of everything. As one acquaintance notes, “She had almost adopted a child.” (The film’s title refers to the fact that Helen didn’t like or use her husband’s first name.)

We also meet Lee’s friend Judith Johnson, with whom he quickly developed a strong bond. As Lee spent more time with her, sometimes neglecting to come home at night, Helen became resentful of being relegated to Lee’s “main woman,” a role she had no intention of fulfilling, as she tells Thomas frankly. Neither woman was supposed to be at Slug’s Club where Lee was performing on that snowstorm-plagued night in February, a fact that makes the resulting tragedy seem all the more random and senseless.

I Called Him Morgan is clearly a labor of love for Collin, whose 2006 documentary My Name Is Albert Ayler was similarly enlightening and evocative. Those who already revere Morgan will undoubtedly find the film fascinating; those who might not be familiar with the artist will probably be inspired to seek out his music.

I Called Him Morgan opens on Friday, March 24, at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

—Marina Zogbi

- 7 years ago

-

With each year the staggering list of shows grows larger, but we’re here to help with this not so shiny, quite diverse list of recommendations to help you sort it all out.

Monday, March 13th

Idgy Dean – The Parlor Room, 88 Rainey St – 7pm

Sylvan Esso – AV Club Presents Just Another Manic Monday @ The Mohawk – 10:45 pm

Girl Pool – Do512 Party @ Hotel Vegas – 1 am

Tuesday, March 14th

Wu Tang Clan w/ Thievery Corporation – ACL Live at the Moody Theater – 11:00pm

The Districts – Buffalo Billiards – 1:10am

Spoon – The Main – 1:00am

Sleigh Bells – Stereogum Party @ Empire Garage – 1:00am

Plastic Pinks – Fine Southern Gentlemen – 2:00am

Wednesday, March 15thMaybird – Taco Bell Feed the Beat – 1:00 pm

The Avett Brothers – ACL Live at the Moody Theater – 11:00pm

Tokyo Police Club – Bungalow – 12:00am

Grandmaster Flash – Clive Bar – 11:00pm

The New Pornographers – Stubb’s – 12:20am

Field Trip – The Market – 1:00am

Thursday, March 16th

Julie Byrne – Pitchfork Day Party @ French Legation Museum – 12:30 pm

Lo Moon – YouTube @ The Coppertank – 3:00 pm

The Big Moon – South by San Jose @ San Jose Hotel – 4:00 pm

BBC 6 Music Presents @ Latitude 30 – 12:00 amBeach Slang – BrooklynVegan @ Cheer Up Charlie’s – 5:00 pm

Pell – Stub Hub party @ Bangers – 6:00pm

Ecstatic Vision – Grizzly Hall – South By South Death – 9:00pm

Girl Pool – Anti- Records Party @ Elysium – 11:00pm

Friday, March 17th

Womps – Sidebar – 12:00pm

DJ Anthony Parasole – Barcelona @ 12:00am

Weezer – Brazos Hall – 12:00am

Gary Clark Jr. w/ The Mystery Lights – Levi’s Outpost – 9:00pm

Dem Yuut & Loamlands – Barracuda Backyard – 8:00pm, 10:15pm

We Are Wolves – Swan Dive Patio – 9pm

Be Charlotte – Esther Follies – 10:00 pm

Saturday, March 18th

Mather Logan Vasquez – Waterloo – 12:00pm

Future Generations – Kebabalicios – 4:00pm

Mister Saturday Night, Justin Miller, Nik Mercer – Kingdom – 8:00pm

Tkay Maidza – Do512’s The Big One @ Barracuda – TBD